- Home

- Clinton Kelly

I Hate Everyone, Except You Page 14

I Hate Everyone, Except You Read online

Page 14

On the flight over, Damon flipped through a Stockholm guidebook he had ordered online, pausing occasionally to ask me to remind him again why we might be moving to Sweden.

“Because Ted Cruz is the devil,” I said.

“You’ve mentioned that a few dozen times,” he replied. It was true. “But why can’t we live in Paris? We love Paris. And you’ve been wanting to brush up on your French.”

He was right. My French was very rusty, and I had been talking about enrolling in a two-week French immersion course in the south of France. But to be honest, the thought of actually going through with it gave me a migraine. “I’m getting too old to be fluent,” I said. “The best time to learn a language is during your formative years. I’ve been fully formed for a while now. At this point I’m well into the decay phase.”

“Okay,” Damon said. “How about Sydney? We love Sydney and you’ve been talking about surfing more.”

He was also right about that. The first time I tried surfing, in Hawaii, I turned out to be a little bit of a natural. I stood up on the board on my first attempt, rode a decent-sized wave, and impressed the hell out of my instructor. But to tell you the truth, I wasn’t too surprised. I had been passively training for twenty years on mass transit. If I can’t get a seat on the New York City subway, I stand, like everyone else. But I don’t like touching the pole with my bare hands because, well, cooties. So, I’ll just sort of stand there with my legs bent and my core engaged, and occasionally flail around like one of those inflatable air dancer things they have outside car washes.

But as much as I would like to hang ten with a bunch of tanned, six-packed Aussies, we couldn’t move to Sydney because of Mary. “The dog, Damon, the dog,” I said. “Australia requires a six-month pet quarantine. Didn’t you even hear what happened to Johnny Depp?” (I was certain he had not.) “Over my dead body will Mary spend half a year in a kennel without me. I’ll sleep in the goddamn kennel before I let that happen. I’ve already looked it up: we can get a dog passport for Sweden. She just needs a few shots.”

We played this game for a solid hour, and I call it a game because neither of us really had any intention of leaving our family, friends, and careers in the United States. It’s just nice to consider one’s options.

Stockholm’s Arlanda Airport is large and bright, with many windows overlooking the verdant landscape nearby. The polished dark hardwood floors, very similar to the ones we have in our house, shine in the natural light. “Look at the sheen on these,” I remarked. “As you well know, these floors aren’t as low-maintenance as they look. They seem like an unwise choice for a high-traffic area if you ask me.” But Damon pointed out the near-complete absence of foot traffic. The people exiting our flight were the only people in the whole airport. Suddenly I was struck by the feeling of what it might be like to survive a zombie apocalypse.

I imagined a sequel to The Walking Dead: It’s been ten years since the last zombie kicked the bucket, for the second time. A small group of Swedes and a highly sophisticated, well-dressed, middle-aged American man, played by me, of course, must reestablish civilization and procreate to repopulate the world. (My character and an adorable twentysomething lesbian, played by Jennifer Lawrence, reproduce via IVF.) Their first task is to clean shit up. They break out the Windex and the Pine Sol and just go to town for, like, the first three episodes, scrubbing, polishing, disinfecting . . .

“Look, ABBA,” Damon said, interrupting my creative flow. He pointed to a life-sized cardboard cutout of the most famous singing group in Scandinavian history. I assumed it was an enlarged album cover from the 1970s, or maybe they still dressed in clingy bell-bottoms. I’m not so up-to-date on my ABBA news. “The one on the left’s got quite the ABBAconda,” I said.

Within one hour of settling into Stockholm—taking a taxi from the airport, checking in to our hotel, unpacking—we realized we were going to be bored to death for a week. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a fine city, pretty enough with lots of old, square buildings. And the food was surprisingly good. We discovered a love of skagen, basically a shrimp salad on toast, and found a place that served the most amazing Swedish meatballs, which I consumed greedily, despite the fact that they contained veal. (I co-organized The Anti-Veal-Eaters Revolt in the eighth grade and never really looked back.) And the fine citizens of Stockholm are excruciatingly civilized, if slightly depressed and—I got the impression—slightly insecure about their city. Practically every local we met asked our opinion of the place.

“How do you like it here?” a salesman in a clothing store asked Damon while I was trying on a sweater.

“The sun is up for a really long time,” Damon replied, and the salesman nodded in resigned agreement.

We took a ferry ride and a nice old man asked us how long we were staying in town. A week, we said.

“Too long,” he responded. “I was born here, but forty years ago I moved to Sydney.”

“We have a dog,” I said. “We can’t do that.” The old guy looked at me as though something had been lost in translation. It hadn’t. I’m just incapable of rational thought around the subject of my dog.

We mostly just walked around quoting Trading Places, one of our favorite movies.

“I am Inga from Sveden.”

“But you’re wearing lederhosen.”

“Ya, for sure, from Sveden. Please to help me with my rucksack?”

On the third day, we decided to visit the Vasa Museum, the main attraction of which is an elaborately decorated seventeenth-century warship, the Vasa, that was so poorly engineered that it went ass over tea kettle and sank on its maiden voyage, right in the center of Stockholm Harbor. Three hundred years later, it was salvaged, reconstructed, and preserved in the museum, a feat Swedes seem very proud of. The museum, or museet, is actually a pretty enjoyable way to spend an hour and a half out of nineteen excruciatingly long hours of daylight.

Exhibitions throughout the museet have been designed to give you a taste of what life aboard the ship might have been like. For example, for 450 passengers, the vast majority being soldiers and sailors, there was one dentist, who was responsible for everything from tooth extractions to limb amputations. If a sailor was disrespectful to the admiral, he could be keelhauled. That’s when they tie you to a rope, throw you off one side of the ship and pull you out the other side, dragging you under the keel of the boat. In the middle of the ocean. For being disrespectful.

“Hey, Admiral, your father’s meatballs are huge and salty.”

“Under the boat with you, Sven!”

“What? I grew up next door to you. He’s a really good cook!”

And maybe even more incomprehensible: two toilets. For 450 men spending their days drinking beer and eating nonrefrigerated meat! Can you even imagine the line for those things after a meal of half-rotten caribou kebabs? I can’t. I’m the kind of guy who gags on an airplane when someone two rows ahead of me farts in his sleep.

Divers also recovered several skeletons of people who got trapped aboard the ship as it sank, some of whom were women. (Historians aren’t even sure what women were doing aboard the ship in the first place.) Based on mineral testing and X-rays of the bones, scientists determined that pretty much everyone had suffered from severe malnutrition as a child or walked with a limp because of injuries that had never healed properly.

In the darkest part of the museet, six heads glow from inside glass cases. They’re creations of forensic artists, facial reconstructions of six skulls found in the muddy wreckage. There’s a blatant honesty and exactness you might expect from a Swedish forensic artist, from the enlarged pores they added to broken capillaries to overgrown eyebrow hair. If this ship had sunk off the coast of, say, Barcelona, I’m sure the reconstruction would have gone much differently. All the dead people would look like Calvin Klein fragrance models on the receiving end of fellatio. But not these old Swedes. They are rough-and-tumble.

Except Beata, whose reconstructed face caught my eye. She was beautiful, in th

at profoundly dejected kind of way. Physically she was a mix of weak and strong features: pronounced cheekbones and a big nose that appeared to have been broken once or twice, small blue eyes, thin lips, and a ruddy complexion. Her blond hair was pulled back from her face, covered by something resembling a folded dish towel. I’ve done so many makeovers in my life that I’m almost embarrassed to admit my first thought was, With a little concealer and the right lipstick, I could make this chick look like Uma Thurman.

But I let that moment pass. I looked at Beata for a while, and she looked at me. Her expression was that of a woman who had been thoroughly beaten down. What were you doing aboard this ship full of men, Beata? I wondered. Were you a stowaway? Were you a whore? Was it your job to clean those two toilets? Was life so bad on land that the sea seemed like an escape? An adventure? And who broke your nose? Some guy you were shacking up with? Your father? Your mother?

I just could not even fathom a situation in which this woman’s life was anything but pure misery. Only thirty or so people died aboard the Vasa. Because it had barely left the dock, most passengers just swam to safety. But why did Beata die? Maybe she got pinned under a table or crate when the boat capsized. Or maybe she couldn’t swim. Or maybe going down with the ship was better than going back to shore.

Tell me, Beata. Tell me!

“Hey handsome.” Damon had walked up behind me. He whispered in my ear, “What are you thinking?”

“Oh, you know, just the usual nonsense,” I said. “How do you feel about picking up and going to Paris tomorrow?”

“I think that is a brilliant idea.”

The Internet service in Sweden is pretty fast, so we were able to book a flight to Paris and a hotel room in the First Arrondissement in less than fifteen minutes. It’s not that Sweden is unlovable, or unlivable, it just wasn’t our cup of glögg.

* * *

Paris, on the other hand, can make you feel like all is right with the world, that every cathedral deserves flying buttresses, every meal deserves dessert, and every pedestrian deserves painful but gorgeous shoes.

Damon and I were walking through the immaculately groomed gardens of the Tuileries when our phones started to blow up. It was June 26, 2015, and the US Supreme Court had just ruled that same-sex couples were entitled to all the benefits of marriage on a federal level. We both teared up. Our lives are nothing short of amazing, filled with people we love and who love us, but sometimes you don’t realize you’ve been a second-class citizen until you’ve received the right to be first-class.

We decided that to celebrate I should post our wedding picture on my Facebook fan page. It’s a candid shot of us taken in our backyard in Connecticut. We’re holding hands as we walk down the stone steps to our pond, where our friends and family were waiting for us. Neither of us is looking into the camera but we’re beaming with joy.

The post received 180,000 “likes” and more than 6,000 people stopped whatever they were doing that day to wish us love and congratulations.

Five people thought it was appropriate to tell us we were going to hell.

If you’ve never been told by a complete stranger that you’re going to hell, let me try to explain the feeling to you. It makes you feel something like sadness, but it’s not quite sadness. Sadness is when your favorite grandfather dies or your parents tell you the dog you grew up with has cancer. And it’s not really anger, because anger is when you see a drunk driver on the highway in front of you when you’ve got your family in the car. And it’s not exactly pity, because pity is what you feel when you pass a homeless mother and her two children on the street. It’s all of those emotions rolled up into one not-yet-named-in-English emotion. But it doesn’t consume you in the fiery way that rage can or the chest-crushing way sorrow can. It’s smaller, subtler, like a thousand shallow pinpricks.

Soon after the marriage equality ruling, Ted Cruz called the day “some of the darkest twenty-four hours in our nation’s history.” And at that moment I realized why I had been having disturbing visions of his face: God wanted me to know, in no uncertain terms, that Ted Cruz is a huge, painful asshole.

And that even if he, or someone just as horrible, becomes president, it’s not worth jumping ship.

THE WAY IT WENT

Clayton,* recently hired as a host for what would prove to be a short-lived home shopping network aimed at an upwardly mobile audience, sat at his desk writing notes on his blue cards for the next day’s show. He had never been good at sitting still for any extended period of time, so his gaze frequently strayed to the plain-faced clock on the wall nearby. It was 4:50 p.m., so he could leave the office unnoticed in a little more than an hour. He had to prepare for a date that night with Tim, a handsome computer programmer with curly black hair he had met at the gym four months earlier.

The casual nature of his relationship with Tim made Clayton anxious. Clayton preferred clearly defined classifications when it came to men he was romantically involved with because they helped manage all parties’ expectations, especially his own. For example, “dating” meant going on dates. Guys who were “going steady” were sexually monogamous. If you were “fuck buddies,” you had regular sex without dinner or emotional commitment. And “boyfriends” were two guys working toward a common goal, like eventually sharing an apartment or adopting a dog. (Where Clayton acquired these definitions, he did not know, yet he regarded them as absolutes. Such is the wisdom of a twenty-five-year-old.)

Clayton/Tim fit into none of these categories. They went on dates that led to sex, of course, but they never talked of a future past Friday or Saturday night, so it seemed to Clayton that they were “dating.” But recently their individual friend clusters had intertwined so that the two groups now attended the same parties, which suggested to Clayton a certain deepening of commitment. Tim had even let Clayton’s friend Fiona hold his penis once as he peed during a party at a stranger’s apartment on the Lower East Side. An intimate act if ever there was one! Granted, Clayton was perplexed as to why a straight woman would want to hold a gay man’s penis—let alone any penis—during urination. And why a gay man would agree to it. And how the hell the topic came up in the first place.

A girl from the office stopped by Clayton’s desk and sat on it, which he found odd. The typical work friend might lean on a colleague’s desk, he thought, or stand there unassisted, honoring the concept of personal space. But he didn’t even know her name, just her face, and that was because she sat along the route to the men’s room.

“Hi, I’m Isabel,” she said.

“Hi,” he replied. “I’m Clayton.”

“I know that, silly. You’re a host. Everyone who works here knows your name.” She had shoulder-length dark blond hair, which was neither sophisticated nor sassy, yet she somehow managed to project that she considered herself both. “So . . . I’m pretty new to town and I don’t really know anyone. Do you want to hang out tomorrow night?”

“Sure,” Clayton said, because he couldn’t think of anything else to say and because he kind of felt sorry for her. New York can be the loneliest place on earth if you’re not careful. It’s surprisingly easy to be overlooked by 8 million people, he had discovered quickly, lest you remind them of your existence on a near-constant basis.

“Great,” she said, dropping a tightly folded piece of steno paper near his keyboard. She hopped down from the desk and strode away, as suddenly as she had arrived.

As Clayton unfolded the paper, which contained Isabel’s phone number as well as her address, he began to feel angry at the way he had been ambushed. That’s not how Saturday night plans were made! You didn’t make Saturday night plans until Saturday afternoon. That was the way it worked in New York. At about 3 p.m. on Saturday, you would call a few friends and set an agenda for the evening that could be amended or canceled at will depending on better offers that may or may not arise. But now he had plans, which interfered with his lack of plans, and made Clayton feel very uncool just as he had been beginning to feel sort of coo

l.

Once home, Clayton showered and groomed and changed into a fresh pair of khakis and the light-blue button-front linen shirt he had bought at Banana Republic for the occasion. Around seven Tim called and suggested they meet for dinner at a small restaurant near his apartment in Chelsea at eight. Clayton took two subways to get there and arrived looking more rumpled than he would have preferred. They had martinis and spoke about their jobs, their friends, and recent parties they thought were either lame or amazing. They also talked about spaetzle. Clayton, who had never heard of it, read it aloud from the menu as spahtz-el.

“It’s shpets-luh,” Tim said.

“Oh,” said Clayton. “Well, now I feel stupid. Should I have known that?”

“It’s like an Eastern European pasta,” Tim said. “You should order it. You know, expand your horizons a little.” He smiled and looked down at his menu.

Clayton didn’t know if Tim was mocking him or being sincere. Though Tim was a few years older, he seemed considerably more worldly. Clayton ordered the spaetzle, which was good, if a little bland. Little did he know at the time he wouldn’t eat it again for another fifteen years, not because he didn’t like it, but because the occasion rarely seemed to present itself. They split the check, and Tim asked Clayton if he’d like to come back to his apartment.

“Sure.”

They walked to Tim’s apartment, immediately undressed and began to have sex (the details of which will be left to the reader’s imagination). About seven minutes in, Tim stopped all movement and said rather matter-of-factly, “I’ve got something to tell you.”

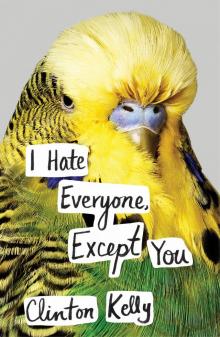

I Hate Everyone, Except You

I Hate Everyone, Except You